The term ‘Product Discovery’ is now an established entry in the standard lexicon of product development, but what does it mean? Surely you just design a product and then build it – why do you need to ‘discover’ it? Is this simply a ruse by research and design teams to keep themselves in work?

Ask anyone who has funded the development of a misconceived product, “If you’d had the chance to get out early and cut your losses, would you have taken it?” You can guess the answer. If you could always predict, at the earliest possible juncture, that a product wasn’t going to succeed, wouldn’t this be the best way to mitigate the risk of investment?

Unfortunately, funders of new product development frequently fall prey to various cognitive biases. Their belief in the project is perceived as conclusive evidence that it will succeed, a form of the Valence Effect. Groupthink can suppress dissident predictions of failure, and the Sunk Cost Fallacy can keep investors throwing good money after bad, long after they should have pulled out.

There is no magic formula for success

In truth, nobody can foretell the future; also, it’s important to keep in mind that the most expensive way to test whether a product should be built is to actually build it. Therefore, wise investors know that there is a possibility that their initial investment will be lost, and they should therefore seek to minimise that loss. This is where Product Discovery first steps in.

The purpose of Product Discovery is to test whether and why a product should be built. Beginning with a known business problem and a high-level vision for a solution, it investigates various aspects of the proposed product to test whether it’s feasible, realistic and economically viable. It seeks to eliminate the biggest risks and areas of doubt and, as far as possible, to validate that the product can and should be built.

How is Product Discovery done?

Many product development projects begin with a discrete, time-boxed Product Discovery phase. The aim is to validate (or otherwise) continued investment in the product.

The key outputs are the elements of a business case for the product to be developed, including:

- Validation of the problem to be solved

- Identified market segments

- Well researched user / buyer personas

- Value proposition(s), articulated as pains relieved / gains realised

- High level features of the product – only those that are distinctive and critical

- Competitor analysis, with a strategy for beating them

- Pricing, revenue channel(s) / monetisation strategy

- Barriers to entry, risks and sensitivities

It’s sometimes necessary to prototype the most risky elements, if they’re critical to the product’s success, in order to establish that they are useful and feasible. You should resist the temptation to design the product up front; prototyping can often be done using low-tech tools to mock up the concept just enough to perform tests. For example, by mocking up a mobile app on pieces of paper rather than using high-fidelity prototyping software, a test can be defined that focuses on a specific line of inquiry and avoids the distraction of irrelevant features.

Product Discovery is a team sport

A world-class Product Discovery will consider all aspects of the product throughout its initial development and, as far as possible, its lifetime. This means that you should take input from everyone involved in its production: product manager, product owner, designers, UX researchers, engineers, testers, and ideally a scrum master or agile coach. Most importantly, you should include your customer: consult with people who represent your target personas and, if possible, bring them into the process.

This not only gives more broadly-considered results to your investigation, it also means that, when the product goes into production, you won’t lose important information or context along the way; also, the team will be more motivated, having been engaged in the product since its inception.

Product Discovery never ends

A Product Discovery phase like this can certainly open the way for funding to start building a product. However, it’s an all-too-common mistake to think that all the questions have been answered at this point. In practice, it’s not possible to foresee all the risks inherent, even in an initial product development. Things get even less predictable once you launch the product to market: real people start to use it (hopefully), and they have a habit of not reacting the way you had expected. They might hate the way a certain feature works, want one that you didn’t think of, or even use the product in an entirely unexpected way to solve a different problem.

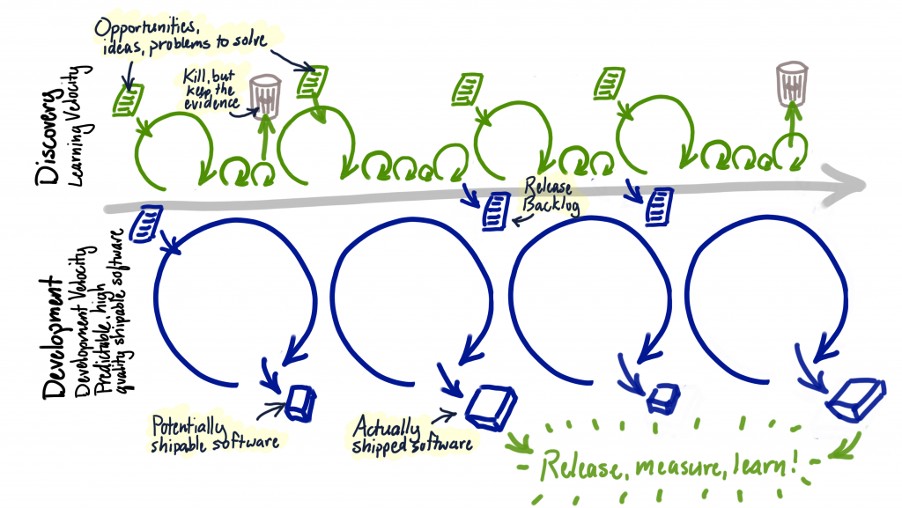

This is why it’s important to see Product Discovery as an ongoing process of continual learning, to include research and prototyping as a normal part of your process. In the agile software development world, this is sometimes referred to as ‘dual track’ agile, a term coined by Marty Cagan and Jeff Patton when discussing Desiree Sy’s 2007 paper “Adapting Usability Investigations for Agile User-centered Design”. This describes the working pattern on which high-performing teams have generally settled, in which research and design takes place alongside build, within the same team but operating as a separate stream of activity, and possibly with a different (or no) cadence.

Working this way shortens, as far as possible, the time spent working on (and therefore investing in) products or features that don’t hit the mark. A failed test is an opportunity to learn and improve. Of course, if your tests keep failing, then you probably have more fundamental problems!

We'd love to tell you more, for free

If you would like to know more about how Product Discovery is used by world-class product firms, drop us a line for a free consultation.

Share

Keep reading ...

Blog 3 min read

December 10th, 2019 - by Olivia Stiles